I've admired Miller's work for years—particularly her groundbreaking wartime coverage for Vogue, which managed to be unflinching, humane, technically brilliant, and visually daring all at once. But seeing her world assembled room by room brought a new clarity to just how radical she was.

The lead image for this post is of her wartime uniform and the Rolleiflex 120 camera that became an extension of her own eye. Presented in a glass case, it's surprisingly modest—no spectacle, no theatrics. Yet that simple kit shaped how millions came to understand the Second World War. Her Rolleiflex, without a zoom, forced proximity. It pushed her physically into the scene. It meant truth had to be faced at close range.

Walking through the exhibition, that intimacy never leaves you.

Experimentation as Identity.

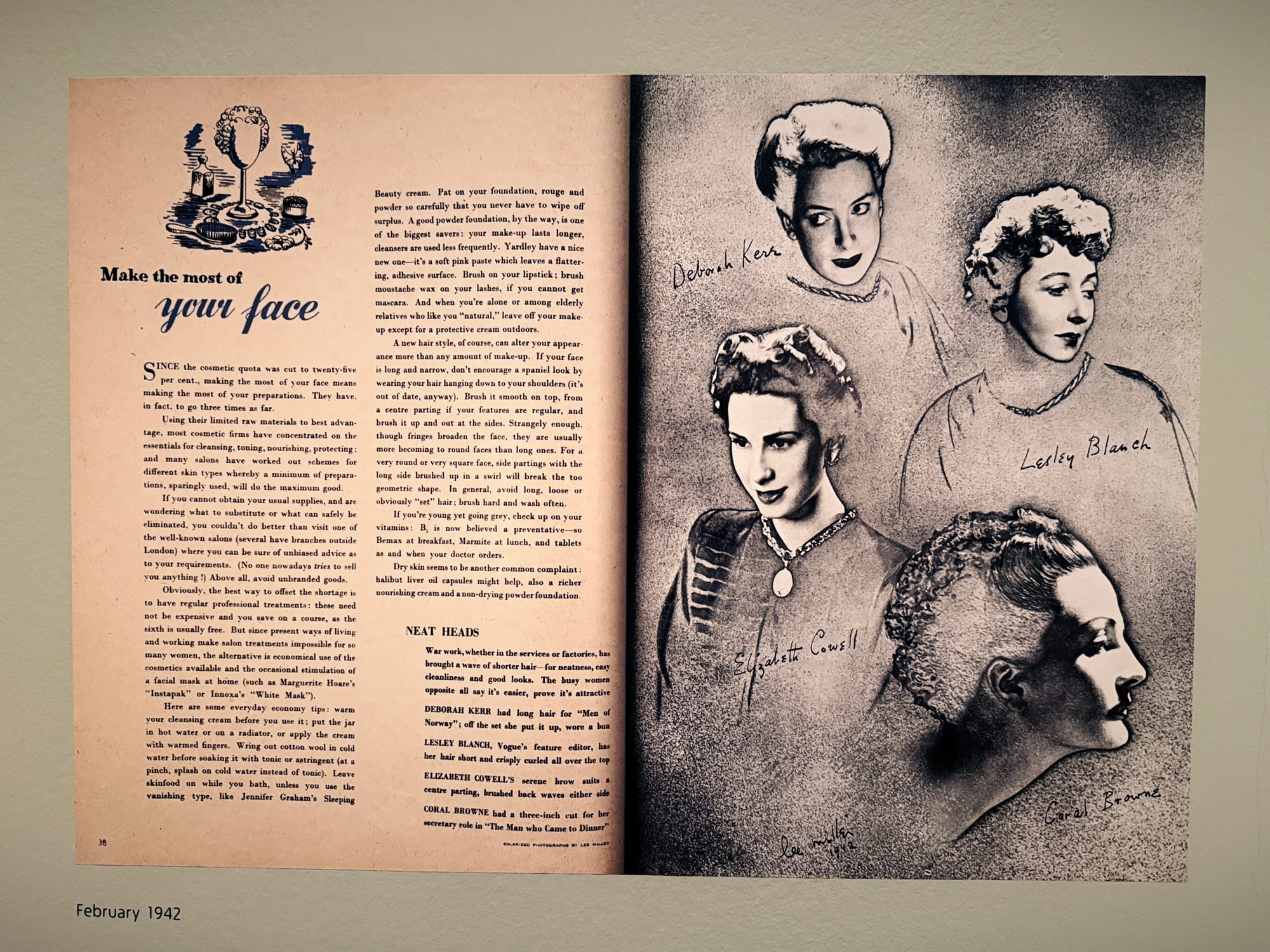

One wall text in particular stopped me: the section on Kodachrome. Miller leapt at new technologies, embracing the vivid, technical challenges of early colour film. She conducted her own research by repeatedly testing Technicolour films, pulling apart colour theory, and understanding how light behaves when asked to tell a new kind of story.

Her first colour image for Vogue appeared in 1943, and her 1944 cover marked a breakthrough for the British edition, finally matching the colour ambitions of its New York counterpart.

Reading that text, I smiled. My own experiments with colour, albeit on a very different scale, come through the Leica Lux app on my iPhone. It's not Kodachrome, and it certainly isn't a Rolleiflex in the mud of Europe. Still, there's something universal in the desire to push tools, to test boundaries, and to chase a feeling rather than simply record a scene. For both of us, photography is first an act of curiosity.

A Room That Asks You to Pause

Halfway through the exhibition, a sign warns visitors that the next room contains graphic images from the concentration camps and asks that no photographs be taken. It's a necessary boundary, and it completely changes the atmosphere before you even step through the doorway.

Miller entered Buchenwald on 16 April 1945 and Dachau two weeks later. Her dispatch to Vogue is as famous as the images themselves:

"I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THAT THIS IS TRUE."

Standing in front of those photographs is different from studying them in books. Her Rolleiflex brings you close—closer than comfort, deliberately so. These images were not made to aestheticise horror, but to remove the possibility of denial. A reminder that journalism, at its best, is an act of moral force.

Seeing the Photographer, Not Just the Icon.

Alongside the devastation, the exhibition shows her quieter experiments, her surrealist collaborations with Man Ray, her portraits of friends, her Cairo period, and the years when she was celebrated yet internally shattered by what she'd witnessed. The exhibition booklet speaks to the toll: her archive was rediscovered only after her death, tucked away in attic boxes.

Something is grounding in seeing the work of someone who never set out to be an icon. She simply chased the image, sometimes as art, sometimes as evidence, sometimes as a way to make sense of a world that stopped making sense.

Why This Exhibition Matters to Me

As someone who has experienced conflict, albeit in a very different era and through a different role, I've always admired Miller's ability to shed light on the tension between restraint and revelation. She understood both the absurdity and the brutality of war.

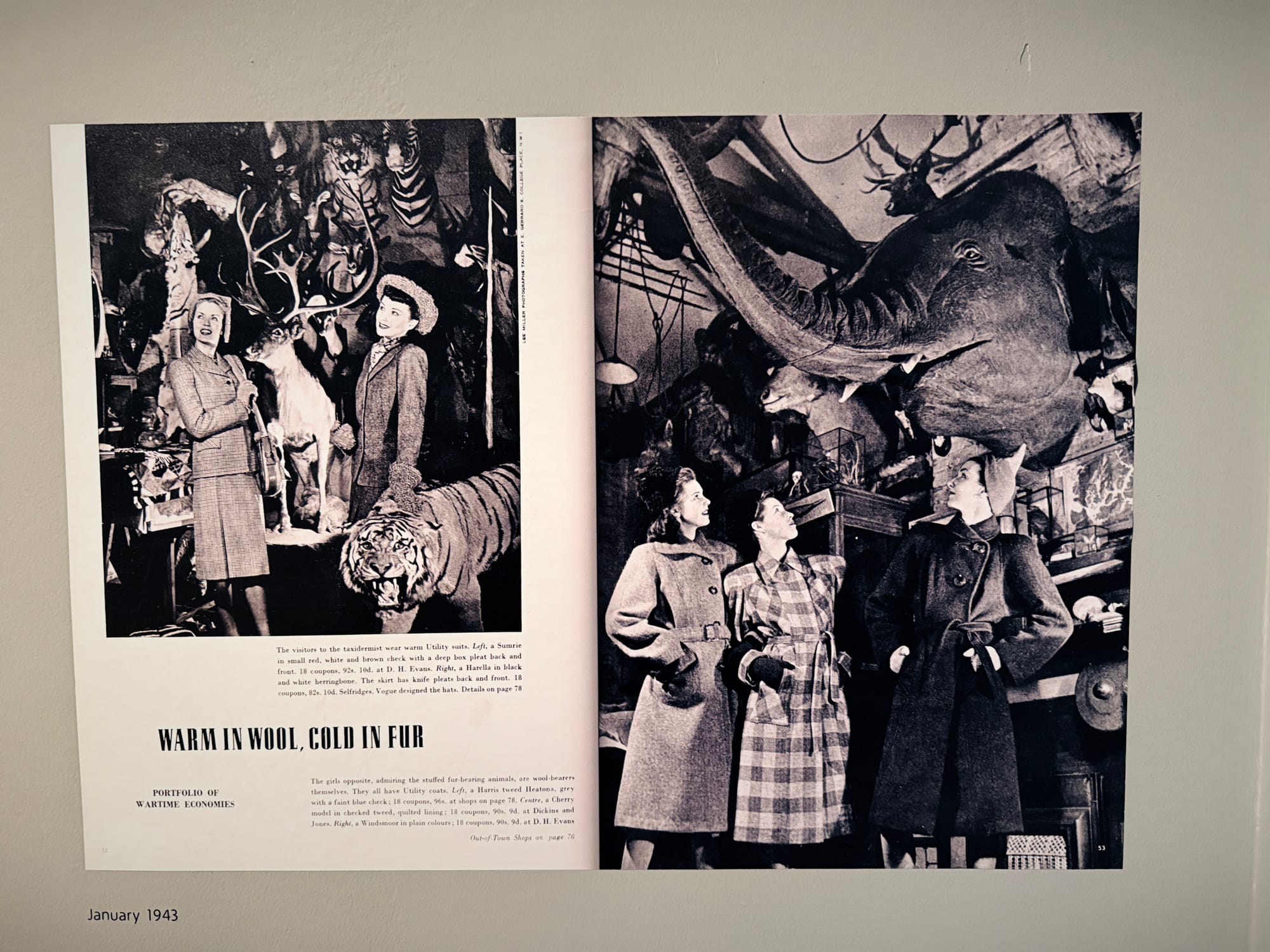

Her Blitz photographs, for instance, captured not just the horror of war but also a surreal sense of resilience: fashion posed against bombed-out streets, with irony serving as a coping mechanism.

The exhibition booklet from Tate describes how British censors discouraged graphic images, prompting her to adopt a poetic style that continues to influence international perceptions of wartime Britain. Additionally, her post-war work, featuring quieter portraits, humour, and moments of fragility, resonates with anyone who has experienced a full life before embarking on a new chapter.

Walking Out Inspired

What I carried away from the Tate wasn't just admiration for Miller's courage. It was a renewed appreciation for experimentation, persistence, and the instinctive act of seeing.

Whether it's her blazing Technicolour curiosity, her surrealist edge, or the defiant clarity with which she documented Dachau, Miller never retreated into safe work. She pushed. She stepped closer.

She made photographs that mattered.

Back home, I scrolled through the images I'd taken on a modern phone, with a digital Leica profile, and realised that the impulse is still the same: to try things, to observe carefully, to find meaning in the unexpected.

That's the connective thread between her 1940s Rolleiflex and my iPhone today. Different tools, same instinct. And that's why this exhibition, for me, wasn't simply a retrospective. It felt like a conversation across time.