When I watched the film again, I was struck less by its satire and more by its discipline. The director, Hal Ashby, directs with restraint, using long pauses and still shots. The rooms seem too big for the conversations inside them. The camera doesn’t hurry to explain; it simply observes. This patience is what the film is really about.

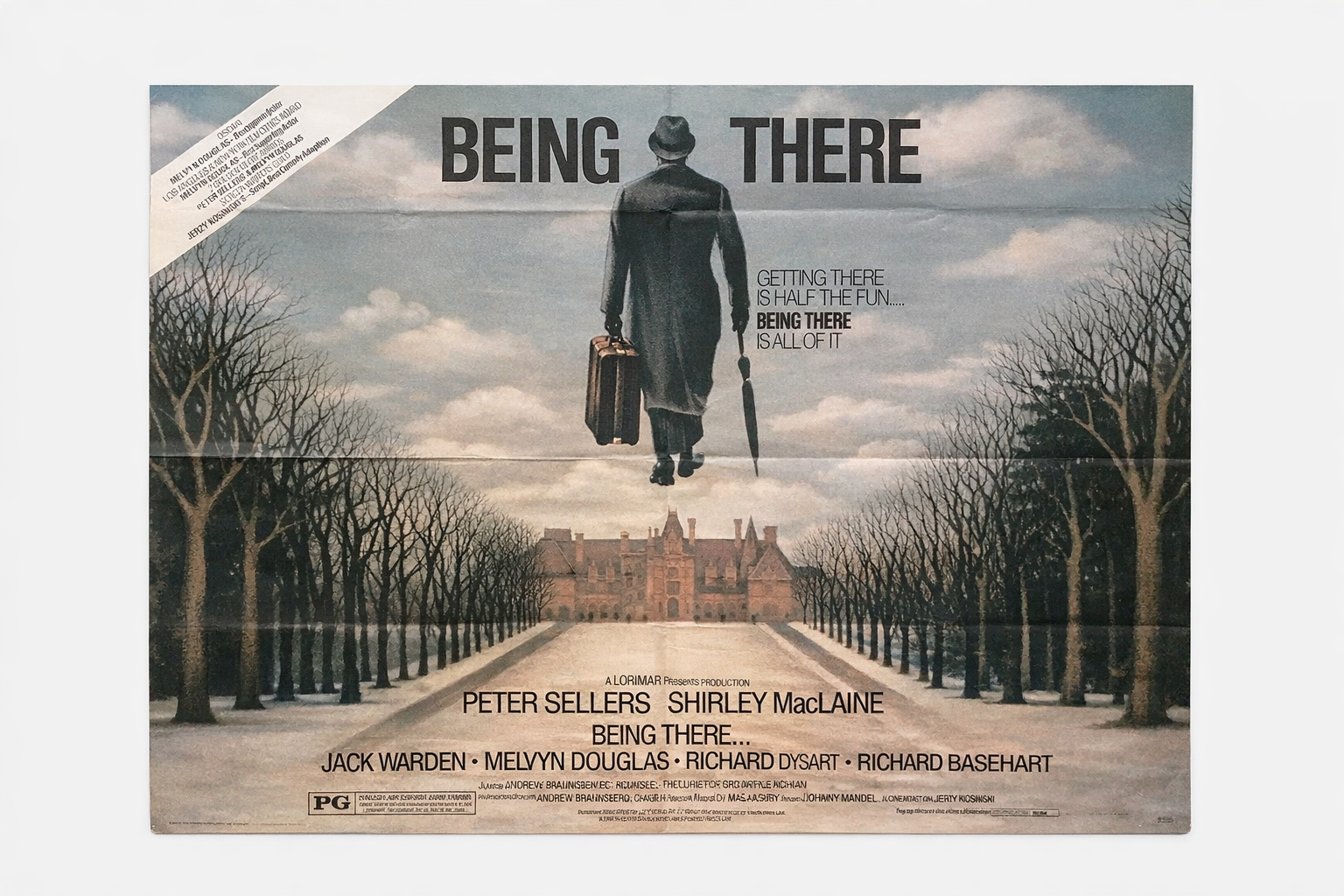

A Film About Surfaces

Right from the start, Being There sets up its visual style. The central character is Chance, played by Peter Sellers, who is the lifelong gardener and caretaker of the house. His world is defined entirely by its routines, rooms, and the television within it.

Chance’s world feels flat, shaped by the television screen. When he first goes outside, the city is filmed with a calm, almost indifferent tone. Washington looks neat, wealthy, and sure of itself. There’s no sense of alarm or chaos. Ashby often puts Chance in the middle of carefully arranged, elegant rooms. There’s dark wood, soft lighting, and a sense of power in how things are set up. These settings signal seriousness and authority. Chance looks like he belongs in these spaces before he actually does in any deeper way. This is important. The film shows that people often start to believe in something because of how it looks.

Performance Without Performance

Peter Sellers plays Chance in a way that seems effortless. His voice stays calm, his posture is neutral, and his face gives nothing away. He doesn’t play up to the camera and hardly reacts at all. This isn’t a lack of acting; it’s a sign of control. Critics often call Chance empty, but visually he is far from it. He is always well-dressed, has perfect manners, and brings a calm presence to rooms full of nervous, talkative men. The humor isn’t in what Chance does, but in how others hurry to fill the silence he leaves.

Cinematic Misunderstanding

One of the film’s most effective techniques is repetition. Gardening metaphors come up again and again. Television clips show up in Chance’s speech. Each time, the same words feel different because the people listening to him change. Ashby sets up these scenes with care. The camera often shows how others react instead of focusing on Chance. We see powerful people nodding, smiling, and leaning in. Meaning is created right in front of us. This is cinema at its best. It doesn’t just show us a lie, but the moment we choose to believe it.

The Ending That Refuses to Explain

The final image is well-known for good reason. Chance walks across water, but the scene is filmed plainly. There’s no dramatic music or special camera work. It just happens, and then the film ends. Critics have argued for decades, and have debated what this scene means. Some see religious symbolism, others see magical realism or political fantasy. The film never picks a side, no one in the film questions it. Just as no one questions Chance’s rise. Acceptance has become automatic. The camera stays steady. The world accepts the impossible and moves on.

A Mirror, Held Late

It’s tempting to compare this film to today’s politics, but Being There is more effective if you hold off on making that connection until the end. The real focus isn’t on a man like Chance. It’s on a system that values comfort over understanding, a culture that confuses calmness with skill, and institutions so used to reading power that they miss when there’s nothing there.

Only at the end does the film quietly hold up a mirror to us.

Donald Trump’s path to the presidency was different from Chance’s, but it took advantage of the same weakness: a media world that mixes up presence with substance, politicians who explain actions instead of questioning them, and an audience ready to see meaning in confidence. As in Being There, the real question isn’t how these figures rise. It’s how calm everything becomes once they are in place.

Being There is still one of the sharpest films about power in a world full of images. It doesn’t shout or warn. It just watches as we talk ourselves into believing.

And then the film fades to black.